- Home

- C. J. Lavigne

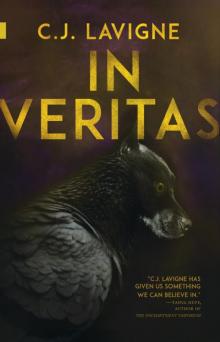

In Veritas

In Veritas Read online

Copyright © C.J. Lavigne 2020

All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication—reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system—without the prior consent of the publisher is an infringement of the copyright law. In the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying of the material, a licence must be obtained from Access Copyright before proceeding.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Title: In veritas / C.J. Lavigne.

Names: Lavigne, Carlen, 1976- author.

Series: Nunatak first fiction series ; no. 53.

Description: Series statement: Nunatak first fiction series ; 53

Identifiers: Canadiana (print) 20190167548 | Canadiana (ebook) 20190167564 | ISBN 9781988732831 (softcover) | ISBN 9781988732848 (EPUB) | ISBN 9781988732855 (Kindle)

Classification: LCC PS8623.A835347 I58 2020 | DDC C813/.6—dc23

NeWest Press wishes to acknowledge that the land on which we operate is Treaty 6 territory and a traditional meeting ground and home for many Indigenous Peoples, including Cree, Saulteaux, Niitsitapi (Blackfoot), Métis, and Nakota Sioux.

Board Editor: Jenna Butler

Cover design & typography: Kate Hargreaves

Cover image uses photos by Jaclyn Clark and Ajay Zula via Unsplash

Author photograph: Berni Scott

All Rights Reserved

NeWest Press acknowledges the Canada Council for the Arts, the Alberta Foundation for the Arts, and the Edmonton Arts Council for support of our publishing program.

This project is funded in part by the Government of Canada.

201, 8540 – 109 Street

Edmonton, AB T6G 1E6

780.432.9427

www.newestpress.com

No bison were harmed in the making of this book.

PRINTED AND BOUND IN CANADA

for Madeline

1

I am writing this for Verity because she cannot write it for herself.

Verity takes pen to paper; two minutes in, her hand begins to shake. She crosses out a word. Rewrites. Crosses out another. Makes an illegible notation. When her fingers spasm and she drops the pen, she crumples the paper and closes her eyes.

She sits at the old typewriter and presses keys with irregular, staccato care. The black lines on the page make her squint. She types a deliberate paragraph before she rips the paper from the machine and shreds it.

She sets a dusty cassette player on the desk and presses ‘record.’ The tape spools and she sits in awkward silence, throat working. She says “Santiago,” and chokes on it. She throws the tape in the garbage.

She touches the computer only once. She pokes hesitantly at the keyboard, averting her eyes from the glowing screen, and exits without saving her file.

She presses herself into the darkest corner of the bedroom closet, and she rocks a little, back and forth. She cannot breathe.

She will look at this and see only all the ways in which it is incomplete.

But this is for Verity. I’ll try.

SEPTEMBER

Verity tells her stories in present tense. She says it lends a sense of immediacy—like watching a play, or characters on a screen. She says it recreates the ‘now.’

So this is Verity, walking down the street beneath overcast clouds and the barest promise of sun. She is still a young woman, but old enough to have a hint of crow’s feet at the corners of her eyes. Her shoulder-length hair is fine and split-ended, seldom combed. It is an imprecisely muddy shade of teak.

Verity is the drab sort of bleached that comes only with fading and time. She is wiry but solid. Her eyes are a grey like sunlit fog, simultaneously bright and opaque, but she seldom meets anyone’s gaze. She has a habit of twitching at nothing, and her lips move as she walks. Though she is clean and nondescript—her black coat well made, her white sneakers unmarred—people sometimes give her spare change.

Today she is watching the sidewalk, and the cyclist who nearly mows her down swears vehemently. Verity keeps walking. She is, in fact, paying attention, but the city is a barrage around her. The sidewalk shadows melt beneath her feet. Each glass tower she passes chimes in her ears. She wavers, briefly, before a window display that tastes of iron and caterpillars; she stares at the rainbow of handbags and perfectly placed leather boots, but her attention skitters to the side and she swallows the raw scent of rotting vegetables.

Only Verity’s world is so dizzying. The cyclist—now halfway down the block, still spitting righteous anger—sees only a woman and a cracked sidewalk, downtown edifices looming glassily above on a cool morning. Brown leaves scatter beneath the tires of his bicycle, and he thinks nothing of it. To Verity, the autumn breeze is a firefly flicker making the street sparkle like rain, but the day is dry and dim and she trudges onward through the minute swirls of light.

When her phone vibrates in her pocket, she stops to answer it and presses her back to a crumbling brick wall. A torn paper flyer scrapes her shoulder, advertising the cancellation of some aborted concert.

“Jacob,” says Verity, gently. Her voice is as grey as her eyes. She hasn’t looked at the caller ID.

“Should we be accountants?” His light tenor in her ear comes a little fast, words as strings impatiently plucked.

In contrast, Verity is quiet for a long moment. She purses her lips; her brow furrows. “I ... what?”

“Should we be accountants? Quick—this guy wants me to do his taxes.”

“We, um—we tried that.”

“We did?”

“Last year. You did it wrong and had to pay that woman nine hundred dollars.”

“Oh. Yeah.” Jacob’s disappointment glides, spider-light, over Verity’s skin. She raises a hand and swipes at her cheek, her eyes tracking the air three feet behind a passing taxi.

“We could—” she begins, but he has already interrupted.

“No, you’re right. It’s cool. Hey, don’t forget the milk, okay?”

Verity brushes her thumb across the screen and slips the phone into her pocket before she resumes walking.

The route is familiar; she is not distracted by the sea-salt taste of the concrete beneath her feet. She turns right at the bakery, pacing under faux-antique lampposts and the glare of tattered flyers (missing kitten!; missing child!!; ONE NIGHT ONLY SALE!!!). It’s nearly noon, and she must share the remnants of the morning with drivers and cyclists and the occasional laughing child.

The crowd thickens at the edges of the Byward Market, near vegetable stands and stalls filled with maple syrup, flowers, and beaded crafts. A magician is setting up near the corner of Sussex and George; he has a faded, collapsible table, a deck of cards, and a dog. The spot he has chosen is shaded by a stone archway between two restaurants—it’s a curious choice for a busker, a dim recess on an already shadowed day.

More, the magician and the dog are both in black: the magician with curling jet hair and a worn t-shirt, jacket and jeans and high boots like an urban pirate, and the dog just a sea of darkness lit by yellow eyes. The magician’s hands are dusky and deft. The dog is the size of a wolf. The magician cocks his head to the left, and so does the dog. The magician fans a deck of cards in his right hand; the dog lifts its right front paw. To Verity, they both smell like sulphur and taste like three hours past midnight, so she stops.

She stands just across the street, near the wall of a bookstore branded in red and gold, and frowns. At first, she thinks the magician is young, but he is too rangy for adolescent sleekness, and the mane of his hair thins slightly at each temple. He tastes so much like the dog that she half expects his eyes to flash gold, but when he and the dog glance over—in fluid accord—his gaze is dark. Both of their s

tares are feral, but the magician returns to his shuffling and the dog watches a moment longer, one ear flicking low before Verity drops her eyes.

When the card tricks start, the magician is neither terrible nor exceptional. He draws the queen of diamonds from a young boy’s ear, but nearly fumbles the ace of spades. He conjures a rose from the air (from his sleeve, really, but he masks it well). The clouds are heavy enough to keep the market crowds light, but the show diverts a modest number of pedestrians. Children watch wide-eyed. Between the rolling crackle of passing cars and the sour-coloured shift of stoplights, Verity makes out the easy rumble of “pick a card” and “is this the right” and “magic word.” The dog sits quietly and endures a small girl pulling at its tail.

The cards only distract for so long before parents begin to tug at children’s arms. The upturned ball cap by the folding table remains empty. The magician weaves and shuffles and smiles, narrow-eyed.

When the first boy takes two steps toward the market, the magician cries, “But wait!” He reaches into the circle of his thumb and finger and pulls forth a gossamer black scarf. It has the look of living shadow, and Verity tilts her head. The scarf drifts lazily in the air as the magician spreads it between his hands.

“My friends,” says the magician, voice still pitched to carry, “are you afraid of snakes?”

The dog paces to sit at its master’s feet, plumed tail high. It is the exact midnight shade of the scarf, and of the magician’s leather jacket. Its untamed gaze rests on eager children and passing cars and Verity’s pale hands.

The magician lets the scarf fly like a banner from his upraised fingers and then drops it, letting it drift down to cover the dog like a shroud. The crowd, curious, now lingers. The boy reaches out for the dark cloth cover, hesitant. The magician waves a magnanimous hand.

There is no magic word—no artistry to the trick, but the young boy reaches into the shadowed arch and pulls at the scarf ’s edge. The scarf slides from the sleek scales of the snake that now curls on the sidewalk where the dog used to be.

The snake has the dog’s black colour and the dog’s golden eyes, now pupiled by reptilian slits. It curls itself into a seething pretzel on the rough ground and flicks its tongue.

A woman shrieks.

They are not looking, the parents and the young children—even the magician, his eyes fixed on the boy, his teeth bared in a grin. They do not see Verity across the street, or the way her stare has focused, or the lumps her tight fists make in the pockets of her coat.

Verity’s world shifts, and only the snake sees.

But the snake tastes like the smoke of fireworks and the deep stillness of night. The crowd gasps and oohs and ahhhs. The snake contorts slowly, in mounded coils.

Verity stands quietly. The magician’s laugh is a sharp report; across the street, he drapes the scarf over the snake again—swiftly, before the sliding scales can spark any kind of stampede, and before the woman with the wide eyes realizes how close that reptile mouth is to her young son’s reaching fingers.

When the magician whips the fabric away, the dog is sitting patiently again on the sidewalk, all wagging tail and lolling black tongue. This time, the audience applauds; this time, a cascade of coins and bills descends into the magician’s hat.

Verity thinks that man and dog both smile.

As phones are drawn from pockets, cameras raised, a third wave of the scarf marks a grand flourish of the magician’s hands; the sidewalk is left entirely empty. The magician, devoid of animals, tucks the folds of the scarf into his sleeve and bows. A few who have just stopped to watch groan in displeasure.

“How did you—”

“Seriously, man—”

“—is the snake?”

Verity is not listening to the awed chatter, the mutters and shaking heads. She stands, hands in pockets, and her gaze is fixed on the magician—not the air, or the dragonfly glimmer of voices, or the buzzing surge of traffic. She stands very still and she stares at the man who tastes of night’s chill. Something about him is ragged at the edges.

He notices her—he quirks a brow in her direction—but the magician is engaged in gracious smiles and murmured deflections. When it is apparent that he really won’t continue, his small crowd begins to depart. The woman with the young son has a tight, angry expression on her face as she tugs the boy toward the market; Verity tastes stale grapefruit and the shallow hint of frustration. One man won’t rest until he’s touched the gossamer dark scarf and shaken it out to ensure there are no canines hiding inside. Another woman gives her small daughter a twenty-dollar bill, and the girl waits with clenched hand and open face until she can tug at the magician’s sleeve and shyly press the crumpled money into his palm. The smile he gives the child glides across Verity’s skin like a fleece blanket.

Verity draws a breath, pausing until the magician is just a lone man standing by a cardboard table. Then, stepping to the corner, she presses the ‘walk’ button at the crosswalk and holds several long seconds for the green. She glances left and right (she is very careful with traffic) and crosses the street. Her footsteps are steady; she studies the ground. She reaches the place where the dog sat, and sees the aging sidewalk is imperfectly patched with a long-crusted piece of gum.

The magician is clearly waiting by then, his gaze as onyx as the dog’s fur and as smoothly impenetrable as the snake’s scales. He stoops to pick up the hat on the ground; spare change jingles and slides. He sets the hat on the table and picks up the deck of cards, shuffling idly. Without looking, he flips the first four cards from his fingers, letting them fall face up next to the battered hat; the aces land in a precise spread, alternating black and red. The magician scoops the cards back into the deck and drops the entire pack into his pocket. “Hello,” he says. His tone is curiosity laced with amusement.

Since his audience has vanished, he is quite probably talking to Verity, but Verity says nothing. She stares at the magician, at the shadow curls and the piecemeal grin and the graceful fall of his sleeves. She licks her lips against the oil-dark taste of his posture; his shoulders are very straight.

He studies the mouse-girl with her uncombed hair. Verity’s stare is intent when she wants it to be.

The magician raises an eyebrow. “Tell me … are you afraid of snakes?” A theatrical wave of his hand conjures a wriggle of blackness from his sleeve—much smaller now, it pools in his palm with a flat golden stare and a darting tongue.

Verity shivers once. “No,” she replies, quietly. “But I’m afraid of this.”

The magician flashes that warm-blanket smile, though his eyes are a wolf ’s, and he sketches a quick, open-handed bow, there on the fractured pavement with the city rising around. The snake writhes from his cuff and curls loosely around his wrist. “He doesn’t bite. Neither do I. Of course, if you enjoyed the show, a small donation—”

“Don’t,” says Verity, a little desperately—she can hear it in her own voice, the sudden torrent of need, the edge of wonder drowning.

The magician pauses, surprised, giving her time to stumble on. Man and snake tilt their heads five degrees to the left, in precise unison.

“Don’t,” Verity tries again, folding her arms tightly over her chest. “Don’t lie,” she says. The magician’s brows draw down and the snake is immobile. To Verity, they both taste of ashes and rotted orange. She shakes her head. “It’s a trick.”

The set of the magician’s shoulders relaxes a little; he chuckles. “Of course it is. That’s the whole point.” He speaks to Verity now as he spoke to the young children—with the soft hint of condescension so often reserved for infants, or the very old. Turning back to the table, he begins plucking soft bills from the hat, folding them neatly. They ruffle as he counts them; he is as deft with money as with cards. The snake remains calmly wrapped around his arm.

Verity stands with her hands in her pockets and her odd stare open and clear; the magician juggles a palm full of change, his posture steadily tensing. He doesn’t watch

her, but the snake does, and the snake never blinks.

“The illusion,” says Verity, carefully, “is the trick. There is no illusion. Your snake is a dog and your dog is a snake is a shadow. If I close my eyes, there’s no difference.”

The magician stills. At his left hand, the impassive snake stretches its mouth wide, and Verity sees a streak of fang.

It occurs to her that perhaps she has not been very wise.

The magician only shakes his head, though he is now studying Verity with a steady intensity that is both perplexed and wary. “You just don’t have the look,” he tells her. “I don’t suppose you’re a fan of the band?”

Verity is utterly nonplussed. “What?”

The magician draws his jacket open and gestures toward his worn t-shirt. It’s a concert souvenir; the date and city are no longer legible, but Verity makes out stylized letters spelling The Between.

Confused, she shakes her head. “I ... I don’t know them.”

“Hm.” The magician twitches the scarf from his sleeve again, and drapes it over the snake. Gossamer falls gracefully over his arm and hand as he sets his attention back on Verity and bows a second time, more deeply. “Abracadabra.” When he whips the scarf away, the dog stands on the sidewalk, ears perked. Its tongue is a streak of midnight against white teeth.

“Don’t.”

She begs the magician with one word, but his smile is as cautious as his eyes. “I don’t believe I caught your name.”

Verity swallows. “Verity. Vee.”

When the phone buzzes in her pocket, she fumbles for it out of instinct; a quick glance downward and she sees the text from Jacob: IM SERIOUS ABOUT THE MILK.

She smells the change in the magician before she looks up. His face is sour. “Huh,” he says, staring at the phone in Verity’s hand. “We’ll have to see about you.”

The charcoal of his voice melds with the letters of the text on her screen, a sudden whirl of shadow and cool electric light that warps across her eyes. Verity swallows the taste of oil and autumn decay. Shaking her head, she feels fear stab through her ribs; she remembers the dog’s sharp teeth but she cannot see.

In Veritas

In Veritas